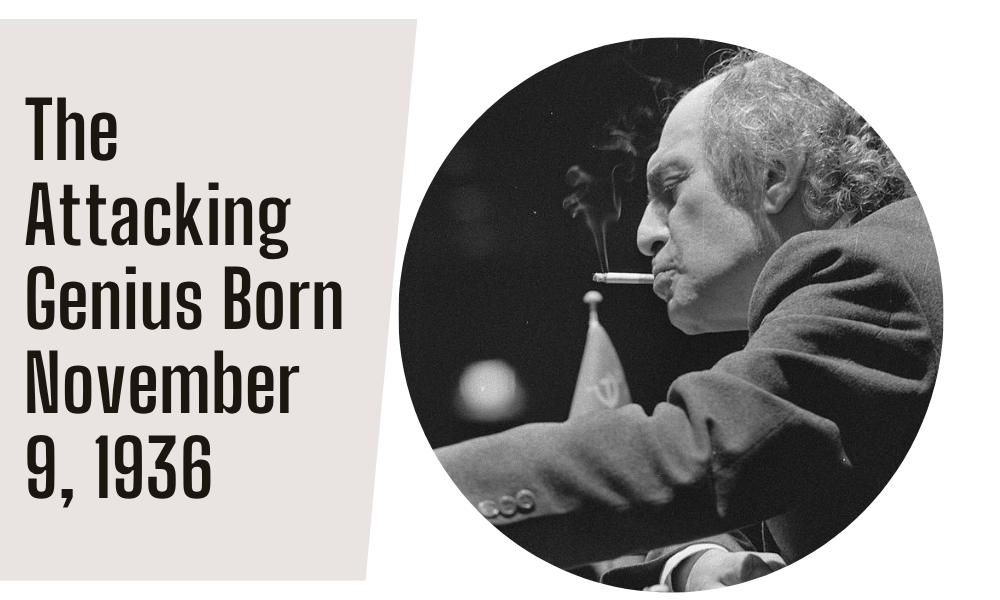

Happy Birthday Mikhail Tal: The Attacking Genius Born November 9, 1936

While the chess world watches 10 Indians battle at the World Cup in Goa, there's a beautiful coincidence worth pausing for: yesterday, November 9th, marked the 89th birth anniversary of Mikhail Tal – the player who proved chess could be poetry.

The Magician from Riga

Born on November 9, 1936, in Riga, Latvia, Mikhail Tal didn't just play chess. He attacked. He sacrificed. He made grandmasters sweat and audiences gasp.

At just 23 years old, in 1960, Tal became the youngest World Chess Champion, a record he held until Garry Kasparov came along. But more than titles, Tal gave chess something it desperately needed: excitement.

The Man Who Made Kings Tremble

Imagine sitting across from Tal. His eyes intense, hypnotic, almost burning into you. Players said facing him felt like being in a boxing ring, not at a chess board. He'd sacrifice pieces like they were nothing, launch attacks that made no sense on paper, and somehow, impossibly, win.

"You must take your opponent into a deep dark forest where 2+2=5, and the path leading out is only wide enough for one," Tal once said.

That was his genius. He didn't just calculate better, he made you calculate worse.

The Beauty in the Chaos

What made Tal special wasn't just that he won. It was how he won.

While other champions ground out positional advantages, Tal threw pieces at your king like a madman. Except he wasn't mad, he was brilliant. His sacrifices looked reckless until you realized three moves later that your king was already dead.

His most famous game? Perhaps it's his Game 6 against Botvinnik in 1960, where he sacrificed a knight with little compensation but prevailed when the unsettled Botvinnik failed to find the correct response. Or maybe it's when Miguel Najdorf allegedly kissed Tal after he made a tremendous queen sacrifice.

The Human Behind the Magician

But here's what made Tal truly special: he was human.

He chain-smoked. He loved jokes and laughter. He was a journalist by profession, writing beautiful prose about chess. He held the record for the longest unbeaten streak in competitive chess history with 95 games between 1973 and 1974, not bad for someone whose sacrifices weren't always "objectively correct."

James Eade listed Tal as one of the three players whom contemporaries were most afraid of playing against (the others being Capablanca and Fischer). But while Capablanca and Fischer were feared for their extreme technical skill, Tal was feared because of the possibility of being on the wrong side of a soon-to-be-famous brilliancy..

Imagine that pressure. You sit down to play Tal, and you know – you know – that if you lose, your game might end up in chess books forever as another example of his genius.

Why We Still Need Tal Today

In 2025, with engines calculating everything to perfection and players memorizing 30 moves of theory, chess can feel...safe. Predictable.

That's why we need to remember Tal.

He reminds us that chess isn't just about finding the objectively best move. It's about creativity. About courage. About making your opponent's heart race.

As one player beautifully put it: "If it were not for Tal I probably would not have been a chess player as I learned chess on the basis of his games and was greatly inspired by his book on his life and games".

A Birthday Gift from History

As 10 Indians battle in Goa right now, perhaps they carry a little bit of Tal's spirit with them. Arjun Erigaisi's aggressive style. Pragg's tactical sharpness. The willingness to complicate, to fight, to create.

Tal lived only 55 years, he passed away in 1992. But his games? They're immortal.

So today, on his 89th birthday, while the world watches the World Cup, take a moment. Pull up one of Tal's games. Watch him sacrifice a piece for nothing but smoke and mirrors. Watch his opponent crumble under the pressure.

And remember: chess is art. And Mikhail Tal was its greatest artist.

Happy Birthday, Misha. The board is quieter without you, but your spirit attacks on.

More to explore:

You must be logged in to comment.